Advent Day 23: Making predictions

Dec 23, 2025

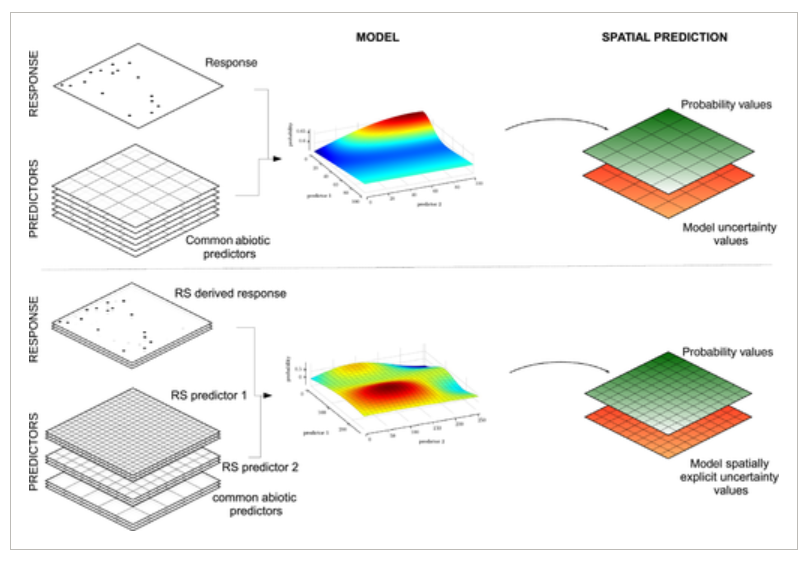

Yesterday’s post focused on linking remote sensing and field data so that pixels or points represent meaningful ecological variation. Today’s post moves from observation to prediction, asking how models use those links to forecast ecological conditions, and why extending predictions beyond well-characterized data is inherently risky.

For instance, while 10 years ago the integration of remote sensing was anticipated to revolutionize species distribution models in He et al 2015, the authors cautioned their use in making predictions in the context of climate change. A quick glance at the literature from the intervening 10 years shows that new methods have been developed to address these challenges and, as anticipated, remote sensing has become an important data source in species distribution modeling development.

Remote sensing models are often used to explain or predict patterns across landscapes and through time, but these goals are not the same. Explanatory models aim to identify causal mechanisms, whereas predictive models prioritize accurate forecasts, even when the underlying drivers aren’t fully understood. As a result, a model can predict variation in NDVI with high accuracy without capturing why those values vary, for example, whether changes reflect drought stress, herbivory or successional dynamics. This distinction becomes especially important when predictions extend beyond familiar conditions.

Not all prediction involves such extensions. Interpolation occurs when predictions are made within the range of conditions represented in the training data. Extrapolation occurs when predictions move beyond that range, and this is riskier because the model has no experience in this new space. These extensions can occur across geographic space, across time or into feature space that was not included in model training.

From an ecological perspective, these extrapolated regions may represent precisely what we are interested in examining. Sometimes, we need to make decisions before some change is fully observed. These new regions may correspond to emerging stressors, novel ecosystem states, potential tipping points. In these contexts, prediction is not about certainty, but about informing action, prioritizing monitoring, and narrowing the space of plausible futures. That said, they are where predictions are most uncertain, requiring explicit diagnostics or uncertainty estimates.

To practice save predictions with remote sensing, making limitations explicit is necessary. This involves:

- Identify the limits of training data: by mapping where environmental variables fall outside the range sampled during model development

- Quantify and communicating uncertainty: usw uncertainty surfaces, confidence intervals or probabilistic predictions

- Treat extrapolated predictions as hypotheses: to guide field verification or experiments rather than as definitive answers

- Incorporate independent data: to evaluate predictions in novel contexts and update models when assumptions break down

Prediction from remote sensing is a powerful tool, but its ecological value depends on understanding where models are grounded in data, where they extend beyond it, and the risks inherent in those predictions. Remote sensing data offer repeated, consistent measurements across broad areas and over long time periods, capturing gradients and dynamics that field data alone cannot. When used thoughtfully, predictions can identify emerging risks, guide management and generate testable hypotheses… but not so much when used uncritically.

–

References

He, K. S., Bradley, B. A., Cord, A. F., Rocchini, D., Tuanmu, M., Schmidtlein, S., Turner, W., Wegmann, M., Pettorelli, N., Nagendra, H., & Horning, N. (2015). Will remote sensing shape the next generation of species distribution models? Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation., 1(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/rse2.7